Control Theory for Distributed Systems: A New View Of Operations At Scale

Greg Boyington (evilchili at gmail dot com)

Abstract

As owners of complex, internet-scale distributed systems, we are often fundamentally surprised by the emergent behaviour of these systems. So-called “inflection points,” when implicit assumptions in the design of these systems are violated by a shift in scale, customer behaviour, or unknown technological limitations, can destabilize our systems in ways that are challenging to recover from. The process of returning a destabilized system to stable when its underlying design principles no longer deliver on the customer promise can be extremely costly, damaging customer trust, jeopardizing business outcomes and sowing chaos in the staff tasked with operating it. Some such inflection points are fundamentally unpredictable, driven by changes to market conditions or new customer behaviours, but many others are predictable within the limits of our understanding of these systems. The better we understand our systems, the more effective we will be in managing them, particularly in periods of destabilization. This paper proposes a new framework for reasoning about distributed systems, drawing on elements of General Systems Theory, Control Theory and Resilience Engineering to help systems owners improve engineering and operations processes and more effectively react to periods of instability.

Background

An Overview of General Systems Theory

General Systems Theory was first proposed by biologist Ludwig Bertalanffy as a new way to do science that rejected the classical reductionism of analysis. To quote (Marsiglia, 2006):

General systems theory is a multidisciplinary approach to understanding theories and principles that apply to many systems. As a biologist, Bertalanffy recognized that there are common principles of organization in various disciplines such as physics, chemistry, biology, and sociology. Consequently, Bertalanffy (1969) developed a set of universal principles applying to systems in general and emphasized that real systems are open to, and interact with their environments. By applying the principles of general system theory, researchers can reduce duplication of effort and leaders can increase their effectiveness in achieving organization goals. (p. 2)

We find that the principles of general systems theory directly applicable to the understanding and operation of large-scale distributed software systems. Following Ackoff (1993) this paper defines a system as the product of the interactions of a connected set of two or more components, the essential properties of which are not shared by those components. In a distributed software system using microservice architecture, we observe that the microservices involved in implementing a customer feature constitute a connected set in which no one microservice in isolation encodes the feature. Consider a web service that allows customers to store and retrieve documents. When a customer requests an inventory of their documents, that request will probably flow through load balancers to a fleet of servers running a web server microservice. The request might be authenticated by a second component service, the inventory calculated by a third, durably stored by a fourth, metered by a fifth, and so on. The ability for the customer to retrieve their document inventory is the product of the interactions of all these components; it is a system, and no one microservice in isolation can deliver the customer their inventory.

General systems theory tells us we cannot understand a system via analysis (Bertalanffy, 1969 p.9). That is, we cannot take the system apart, interrogate its individual components, and arrive at an understanding of the system as a whole. A detailed examination of the request authorization service will never tell us anything about customer inventory retrievals; neither will an examination of the retrievals system absent the customer make any sense. Analysis will tell us how a component works, and we can aggregate this knowledge of individual components to gain knowledge of how the system of which they are a part works. But analysis can never tell us why that system works the way it does.

In systemic thinking, instead of reducing a thing to its elemental parts as we do in analysis, we seek to understand the containing system of which it is a part, and its relationship to that containing system. We can examine each component in the request path of our customer’s inventory retrieval request to build a picture of how the request is handled by our service, but no deep dive into the request authorization component service will ever reveal to us why we get inventory retrieval requests, or why we get them at the rate we do. To understand the behaviour of a distributed system, to be able to say why it works the way it does, we must first identify the larger containing system of which it is a part, and we must identify our distributed system’s function in that containing system.

Analysis, reducing a system to its elemental components, will tell us how the system works, imparting us knowledge. Synthesis, identifying a system’s function within its containing system, will tell us why it works the way it works, imparting us understanding (Ackoff, 1993). This is an important distinction that we will apply in the discussion that follows.

A Note on Resilience Engineering

The emerging focus on resilience engineering as it applies to software is a relatively recent phenomenon; it is still almost entirely unknown (Allspaw, 2019). As such there are opportunities to discover new areas of research, and while this paper does not focus on the principles of resilience engineering per se, we do discuss how the application of control theory to the operations of distributed systems can help address the goals of resilience engineering, that is to practice resiliency as an organization.

Hollnagel (2016) states:

A system is resilient if it can adjust its functioning prior to, during, or following events (changes, disturbances, and opportunities), and thereby sustain required operations under both expected and unexpected conditions.

Given this definition, to practice resiliency an organization must continuously prepare for the unexpected by investing in adaptive capacity before it occurs and respond to it when it does. The model proposed by this paper provides one framework for identifying opportunities within an organization for greater adaptive capacity through enhanced observability.

Control Theory For Operations of Distributed Systems

In order to fully understand a distributed system we must be able to describe all possible interactions between its components, as well as its interaction with the components of the external system. In Control Theory we have two attractive models for this purpose: the closed-loop feedback system, and the open-loop feedforward system. Feedback control, in which control signals for the system are emitted from within the system based on its own output, is a useful model for understanding the behaviour of distributed systems comprised of multiple software and human agents, particularly as it addresses the notion of stability; this is the model with which we will chiefly concern ourselves in this paper. That said exploring the application of feedforward control — in which a controlling signals are emitted from sources in the external environment without measuring output of the system — is a promising area of future study.

What follows is an attempt to apply the fundamentals of Control Theory, particularly feedback control systems, to describe the set of possible interactions between components in a distributed system. Where we will diverge from classic control theory is in our inclusion of both human and non-human agents in our systems model, following the principles of resilience engineering (Hollnagel 2016). This is necessary because both engineering and operations are manual processes, and as such must be considered humanistically. Quoting Allspaw (2019), “Resilience is something…that a system does, not what a system has. It’s not a property, it’s not a state.” Our goal is to improve the operation of our systems by making it easier to return to stability after periods of instability. That is, our goal is resiliency.

Definitions

Because we are operating at the intersection of control theory and human factors, the mathematical models that underpin classical control theory do not actually apply; thus we have selected terminology that diverges from the literature, but which will enhance understanding of the application of theory to our domain.

SYSTEM: The product of the interactions of a connected set of two or more ACTORS.

ACTOR: A component in a SYSTEM which is capable of effecting the behaviour of the SYSTEM. May be a software agent, hardware agent, engineer, customer, or another SYSTEM. ACTORS constitute a connected set; no ACTOR is isolated.

NODE: An ACTOR which executes some process; sometimes it consumes INPUT but it always generates OUTPUT.

COLLECTOR: An ACTOR which consumes NODE OUTPUT and generates TELEMETRY.

CONTROLLER: an ACTOR which collects TELEMETRY and generates CORRECTIONS.

SUBSYSTEM: A SYSTEM which acts as a NODE in an EXTERNAL SYSTEM.

EXTERNAL SYSTEM: The SYSTEM that contains a SUBSYSTEM.

INPUT: A signal issued to a NODE which informs its process (eg. a synchronous API request; an asynchronous work item)

OUTPUT: A signal generated by a NODE as the result of its process (eg. stack traces, logs, metrics, API requests to other NODES, mutated work items, etc)

TELEMETRY: a grouping of signals that describe the internal state of one or more NODES based on their OUTPUTS (eg. time series, dashboards, alerts, customer reach-outs, post-incident analysis findings, etc)

OBSERVABILITY: the measure of how easy it is to answer questions about the internal state of NODES using TELEMETRY.

CORRECTION: A mutation of one or more NODES in a SYSTEM generated by a CONTROLLER (dynamic configuration changes, mutations of queues, changing network paths, scaling fleets, deploying code changes, etc) in response to TELEMETRY.

STABLE: A STABLE SYSTEM is one in which all NODES are generating predictable OUTPUT given all possible INPUT, over time, forever.

CONTROL: The degree to which CONTROLLERS are able to mutate the SYSTEM with CORRECTIONS in order to stabilize NODES.

ROBUST: The degree to which a SYSTEM will automatically self-correct for predictable instability.

RESILIENCE: The degree to which CONTROLLERS can enact CORRECTIONS for unpredictable instability, and leverage unpredictable stability to extract useful work.

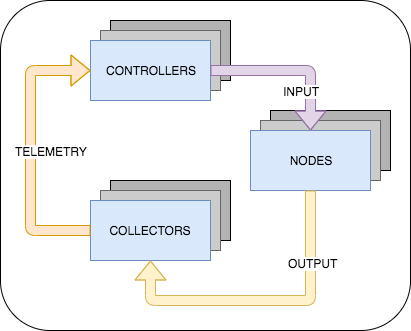

Figure 1. A diagram of a system showing the relationship between actors of multiple types and the flow of signals between them. Note that unlike classical control theory in which a single process variable is controlled by corrections generated by comparing error rates against a reference, actors are a many-to-many relationship in this system. We may have several controllers consuming telemetry and working independently to issue corrections to multiple nodes, or even the same node.

Axioms

- Not all actors are predictable.

- If not all actors are predictable, not all input is predictable.

- If not all input is predictable, not all output is predictable.

- If not all output is predictable, telemetry can never perfectly describe the state of all nodes.

- If telemetry can never perfectly describe the state of all nodes, observability is finite.

- If observability is finite, so is control.

- If control is finite, so is stability.

Discussion

We earlier stated that our goal was to improve the stability of our service. Using the definitions above, this goal can be formalized thus: we wish to maximize stability of our systems to the limits of our control. If our systems lack stability, it is because we lack control. Quoting (Mayr, 1969), “A feedback control system is a system which tends to maintain a prescribed relationship of one system variable to another by comparing functions of these variables and using the difference as a means of control.” Thus if we lack the ability to precisely measure the relationship between the input into a system and its output, we lack control. Using our definitions we say that given some input, nodes may become unstable and produce erroneous output. That output is consumed by collectors, which measure the error rate and expose it to the controllers, which must issue corrections so that nodes are stabilized.

Classical control theory deals with time-invariant, single-input, single-output systems (Zhong, 2004, p. 283). Our model extends this to consider multi-input, multi-output systems, in which parallel feedback control loops may be operating autonomously within the same system. That is, controllers are not coordinated, and the interactions of corrections issued by uncoordinated controllers may themselves yield surprising behaviours divergent from expectations. And of course even a single controller issuing corrections based on faulty telemetry can be a source of instability.

But telemetry is not enough; telemetry that goes unused contains no value and if we lack operational tooling or processes that can adapt to changes revealed by telemetry, recovery is impossible except through chance. Therefore we want systems with automated controllers that can issue the appropriate corrections when predictable instability is detected (robustness) and human controllers who can both improvise successfully when instability is unpredictable and anticipate further improvisations once stability is restored (resiliency).

Defining Stability

Recall from our definitions that a stable system is one in which all nodes are generating predictable output. In classical control theory we might say that nodal output is always bounded for all bounded inputs (the boundaries are predictions about expected behaviour). Notice that this does not encode any notion of fault or error. As owners of distributed systems at scale we know there will always be some error rate greater than zero and accept that this is so; failures are a given and everything will eventually fail over time (Vogels, 2016). We therefore assert that errors do not create instability; surprising errors, and expected errors at a surprising cadence create instability. If we can accurately predict the behaviour of a system, we can anticipate its failure modes and empower controllers with appropriate corrective actions to ensure a return to stability.

When we make explicit those predictions by establishing Service Level Objectives (SLOs) or Service Level Agreements (SLAs), when we create alerts based on monitoring telemetry, when we set team goals around ticket counts, when we define criteria for what triggers a formal post-incident analysis, we are creating a functional definition of stability for the system. Consider the statement “We expect one-minute fault rates to be between 0.0 and 0.001 for any fifteen minute sample.” This is a prediction about our system’s internal state over time, and if that prediction is violated, we might consider the system unstable. But we understand that at scale all services exhibit less-than-perfect availability, which is why we don’t immediately page someone for a single datapoint that violates that 0.001 threshold. In other words, as we predict that fault rates will sometimes fall below typical, our definition of stability must also depend on making a prediction about just how often this will occur. Do we predict 1 page per week? 10? 50? How often do we predict we will break our customer promise? How often do we predict we will fail to meet their entitlement, and under what conditions?

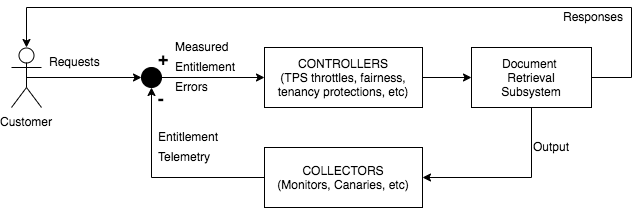

Figure 2. A block diagram of a negative feedback loop in which TELEMETRY is used to measure when a customer has exceeded their entitlement, and combine this with incoming customer requests to make necessary CORRECTIONS (rate-limiting the customer calls, eg). This makes INPUT predictable, keeping the subsystem node STABLE. If the system lacks the ability to make CORRECTIONS, or cannot identify what CORRECTION is appropriate due to limited TELEMETRY, a customer exceeding their entitlement may destabilize the subsystem.

Creating a Predictive Operations Model: Why Observability Matters

The most common state for any owner of a real-world distributed system is to have an incomplete, out-of-date, and inaccurate predictive model of their system. Distributed systems are complex, and complexity yields emergent behaviour; it is not possible to perfectly predict every behaviour of a real-world service. Moreover, the system which contains not just our service but customer use cases, market dynamics, and business goals is similarly complex, unpredictable and changing; the essential properties of our service are therefore also dynamic. Thus our operations model is comprised of predictions of two types: predictions about nodal output that describe the expected behaviour of our current implementation, and predictions about outputs of our system describing its expected behaviour as a node in its external system. Both are informed by, and limited to, the telemetry our system produces. Therefore as owners we must facilitate an adaptive, dynamic operations model by continuously investing in and improving observability. Observability into the behaviour of the current implementation will permit us to increase robustness via engineering and resiliency through adaptive operational capacity; observability into the function of our service as part of a larger system permits us to detect when our current implementation no longer matches the system’s essential properties.

The next sections examine the process of quantifying a service’s extant predictive model by first defining the system that models the service and the system that contains it; identifying its actors, and enumerating whatever predictions about their behaviour currently exist.

Identifying all Actors in the System

This is a scoping exercise. We start with asking the question, “What system are we working on?” For small services, that might be the entire service. For complicated services, that may be a specific workflow. Consider a database product: there certainly exists a system that describes the service in its entirety, which exists within the larger customer/market/business system. But within that product there also probably exists distinct logical subsystems: a create path, a read path, a put path, and a delete path. We might decide that the “get” path including all read operations is one system, and the “put” path which includes all write operations is another. The nodes we include in our system definition depends on where we observe the systems’ essential properties: If the get and put paths are fundamentally different for customers, with different operating constraints and dependencies, different entitlements, and different performance characteristics, it is useful to consider them as separate systems even if they share some of the same actors (the web server, the load balancer, the storage subsystem, the oncall engineers, and so on).

Once we have identified the system we care about, we must list the actors involved in that system. Starting with nodes we ask, “What actors can change the behaviour of the system?” To continue with our database product, it’s every microservice involved in handling an incoming request, plus upstream service dependencies, plus any asynchronous, periodic actors like patch agents, deployments, fleet management tools, backups, and so on. Anything that takes input, executes some process that can alter the behaviour of the system and yields output is a node, regardless of logical, physical and organizational boundaries.

We can identify the collectors by tracing the consumption of node output: the actors that consume metrics to generate monitors, the canaries that consume API responses to observe the customer experience, the oncall tools that aggregate and parse logs to generate realtime statistical trends, and so on. Anywhere a human actor would go to look for answers to “why is the system behaving the way it is,” over any time scale, is a collector that is emitting telemetry.

Controllers may be identified by tracing the consumption of telemetry: systems which take automatic action in response to monitors going into alarm, throttling subsystems which react to entitlement telemetry from other nodes, workload prioritization algorithms, automated software patching systems, and CI/CD tooling. Many controllers of distributed systems are people: they consume telemetry in the form of dashboards, alerts, trends analysis, customer reach-outs, post-incident analysis and other vectors in order to detect instability and correct it. The most important controller of any service and the one working at the smallest time scale is the oncall engineer, because they only begin receiving telemetry when all other controllers have failed to correct for ongoing instability.

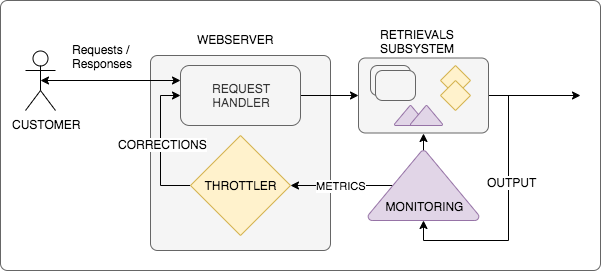

One final observation: for distributed systems of even modest size, it is common to find* *subsystems contained within actors that can act as controllers or collectors. For example, a common behaviour for a web server is to implement customer request throttling, to protect the system as a whole from workloads that threaten to impact other customers. Handling the customer calls and issuing responses is the web server node’s function in the system, but throttles are a controller: they consume telemetry (the customer’s call rate over time, system load and capacity monitors, entitlement consumption and costs…) and make decisions that may result in a correction (throttling the customer for a period of time).

Figure 3. An exploded view of a distributed system in which the webserver service consists of both a NODE (the request handler) and a CONTROLLER (the throttler). The retrievals subsystem node is comprised of many NODES, COLLECTORS and CONTROLLERS, each of which in turn may also contain other NODES, and so on. And the entire distributed system itself is a NODE in a still larger SYSTEM.

Predicting Node Output

For every node in a system, we make predictions about the output of the nodes given all possible input. This process is fundamental, though often implicit, to the entire product lifecycle: at design time it informs the decision to choose between competing possible implementations; at development time predictions are made explicit in the form of integration, acceptance, and load/performance testing; in an operational review we use game days, dry-runs, limited rollouts, private betas and other tools to collect telemetry and codify our predictions about how the system will behave in production; and when a product is finally launched we continue to refine that model and improve our predictions, frequently in the first few months as a real-world baseline for stability is defined, and periodically after that. We encode those predictions in our collectors, updating them when new telemetry from production causes our predictions to change. These are (some of) the places to look for predictions being made about nodes in a system:

- Design documents;

- Alerting thresholds;

- Service Level Objectives;

- Service Level Agreements;

- Recovery Time Objectives;

- Throttlers and other rate limiters;

- Caches, especially eviction strategies;

- Integration Tests;

- Acceptance Tests;

- Performance/Load Tests;

- Chaos/Safety Engineering Tests;

- Game Day plans;

- Canary coverage;

- Post-Incident Analyses;

- Change management procedures, especially validation activities;

- Team Backlogs; and

- Engineering Roadmaps.

We will find predictions about the behaviour of specific nodes in a system in all of these places, and while some will be concrete, functional predictions like a monitor’s alerting threshold, others may be vague or even notional, like an estimate of bandwidth consumption assuming current traffic growth patterns for the next year. Some predictions will have strong telemetry associated with them, such as stack traces, low-level timing and performance metrics, and alerts; others may have no telemetry at all, meaning our observability into the nodes about whose behaviour we are prognosticating is deficient.

Whenever production telemetry deviates from our predictive model (whether because node output contains unexpected errors or because expected errors are occurring at an unexpected rate) we say the system is unstable. But these events should be exceptions; a stable system should consistently align with our predictions. If it doesn’t, either the implementation has a defect, or our predictive model is incorrect and our definition of “stable” needs rethinking. To validate our working definition of stability, we must apply it to historical telemetry for the service and measure how often the system in production exhibits the behaviour our model predicts. How often do retry counters align with the availability model of our dependencies? How often do operating metrics like latency, TPS, load, and failure rates fall within limits established in our SLO? How often do we fail to meet our SLA? How often does the system require manual intervention to restore stability, and do those incidents align with known limitations of the system as designed?

Once we know the degree to which our predictive model actually describes observed reality, we must next ask, for those areas where reality deviates from our expectations, why is this so? What assumptions are inherent to our predictions that are inaccurate? What has changed? This process is described in the next sections.

Predicting Subsystem Output In The External System

What predictions does the external system make about the output of our service, and where will we find these predictions? Many of the same places as our own internal predictions, to start: Alerting thresholds, SLOs, SLAs, RTOs, performance/load tests, game days, and so on are commonly found in the external system, though often these are aggregates that consider output of many subsystems. And like our own internal predictive model, this larger model can be assessed for accuracy by applying it to historical data.

The key difference for owners of subsystems is that if these predictions do not align with the observed reality — if our subsystem is in fact unstable in the external system — this could be an indication not of defects in implementation but that the implementation of our system no longer aligns with the required function of that system.

This can be a difficult concept to grasp, so to illustrate let us consider a service that has been in production for a year or two, and has had modest success. It is not yet profitable, but buzz is good and the market seems interested, but that interest has not yet translated into the growth projected when the service was designed. After a year or two of operations, owners of this system should feel pretty comfortable with their predictive operations model; they know where the system is fragile, they know which nodes are likely to destabilize the most, and why. Now suppose that market research reveals that the major blocker of growth is price. The difficult decision to reduce prices to spur growth despite already being in the red is made, and it is wildly successful: customers onboard with the service in huge numbers and revised growth projections are off the charts. But this success comes with a cost: the service is growing so fast that even under optimal conditions, when every node in our system is working well, it simply cannot keep up with the volume. Architectural limitations which were theoretical just months ago if they were identified at all are now regularly causing the service to destabilize, and because the operations model did not account for this, there are no corrections to be made; oncalls are being paged and there is nothing they can do to stabilize the system. Responding to this scenario requires asking a different set of questions, among them, “Did we build the wrong thing?”

Correcting Predictive Models

When we have identified that our current operations model does not align with the observed behaviour of a system in production, we must revise our predictions. If we do not, our corrections will be inefficient at best, and further destabilizing at worst. Oncall engineers, given a runbook that does not describe the state of the system they see (assuming a runbook exists at all) will improvise, but without strong telemetry describing the internal states of the nodes, their improvisations will be little more than guesses and Recovery Time Objectives become meaningless.

Worse still, a predictive model that is wrong will create noise in our telemetry: alerts become untrustworthy because they fire when they shouldn’t and are silent when they should. Ticket queues are full of non-impacting tickets that mask real issues. Teams focus on the wrong engineering and operations improvements, wasting limited resources on tasks that do not produce meaningful improvements to stability. And so on. Controllers that issue unpredictable corrections inject unpredictable input into nodes, which yield more unpredictable output, leading to further unpredictable corrections, and so on; entropy reigns. Operating a system with a bad predictive operations model creates more instability, and no amount of realignment of resources, increases in headcount, or “crisis mode” operations will reverse this.

Correcting a bad predictive model where good telemetry is available but being ignored is straightforward: close the feedback loop and make engineering and operational improvements based on the telemetry. Improve test suites, adding new tests encoding specific predictions about systemic behaviour that were absent, and removing those which do not manifest in production. Refine alerting strategies: revisit thresholds, deduplication strategies, suppression and aggregation signals, and so on. Update runbooks to address predictable failure modes, delete those which address failure modes removed through engineering improvements, and write new ones. Realign growth targets to consider the requirements of scaling (or rearchitecting!) the subsystems.

Correcting a bad predictive model without good telemetry is impossible. We must be able to ask questions about the internal state of our nodes, and get answers with some degree of accuracy, before we can predict what the system will do given any input. Ensure your nodes are emitting needed metrics, and that those metrics are being consumed and exposed in the appropriate channel. Add tooling to identify patterns in and extract meaning from logs. Make sure product and engineering roadmaps are aligned and stay aligned by facilitating regular, consistent feedback of operational telemetry to product management teams. Surface self-reported operator health to management. Build a database of shared knowledge from the results of post-incident analyses and refer to it when doing design, test plans and operational readiness reviews. Conduct game days to learn how the system actually behaves. All of these are channels for the measuring nodal output and expressing those measurements as telemetry to controllers.

Aside from improving the existing predictions in our operating model, it is equally important to make new predictions in places where we make no predictions about our nodes at all. Often this is a reactive process, as when fundamentally surprising behaviour reveals gaps in our observability forcing us to conduct post-incident analyses and ask questions like “How did this surprise us,” and “How did this behaviour emerge from the interactions of these nodes?” Once a new understanding of the system has been achieved, we can identify telemetry that failed to include existing nodal output, as well as information about the internal state of a node which was invisible in its output which needs to be exposed. Examining past incidents of instability to see what questions were asked, which could be answered and which couldn’t is an effective method of identifying areas of poor observability.

Dealing With Instability

The response to any observed instability follows this sequence:

- Determine what is happening

- Determine why it is happening

- Determine what corrections are required

- Encode this understanding into a controller

- Allow the controller to execute the corrections

- Repeat 1-5 until stability is restored

When telemetry reveals that nodes are destabilized, we start with asking two questions: what is happening? and why is it happening? Identifying what is happening is the job of our collectors, which are consuming nodal output, applying our predictive model, detecting deviations and exposing this as telemetry. Understanding why it is happening requires not just nodal telemetry but a synthesis of the larger system. This is a human process, always, whether it begins during incident response as part of an oncall’s dealing with a customer-impacting event, or in a post-incident analysis, or in a regular review of dashboards and metrics.

Sometimes a human receives telemetry indicating instability, but that telemetry alone does not answer the why. This is a defect in a collector, forcing humans to go and collect other nodal output in order to complete their understanding of the state of the system. Every time this occurs, the collector’s defect must be recorded and addressed. In practical terms this might mean changing the structure of alerts, or surfacing relevant data as part of the alert, or building a dashboard that collates multiple vectors of telemetry into a single signal. Once the why has been established, a controller may issue a correction (or series of corrections) to address the instability, measure the effectiveness by consuming updated telemetry, and repeating the process until the system returns to stable.

Types of Corrections

There are as many types of corrections as there are causes of instability. Non-human controllers can issue corrections by mutating a cache, by throttling incoming requests, by scaling a fleet, and numerous other automated actions. However, since humans are required to answer questions about why this or that node has become unstable, it is impossible for non-human controllers to issue appropriate corrections until humans have encoded this understanding into the controller; as operators we must encode the rules of when a correction is appropriate into the controllers themselves. The more we do this, the more robust our systems become.

Humans are also controllers. When they issue corrections, it might take the form of code changes: fixes and enhancements to either the unstable node, or other nodes in the system which generate the unexpected input, or both. It might take the form of manually mutating a blacklist or whitelist, to influence what gets passed between nodes. It might be simple actions like restarting a process or redeploying a container, or it might be a complicated series of corrections enacted in parallel across multiple nodes or even multiple systems in the external system. The more effective humans are in this process, the more resilient our systems become.

The more types of corrections that are available to controllers, both human and non-human, to use when responding to periods of systemic instability, the more control we have of the system.

Observability for Incident Response

Observability is not something we do, it is something we have; it is the measurement of the quality of our telemetry. Many times the kind of rigorous, structured synthesis of extant systems outlined in this paper is only conducted of necessity, notably when systemic instability has gotten bad enough to page oncall engineers who are now trying to make sense of the confusing mix of signal and noise in their telemetry to determine what is happening, why, and what to do about it.

It is fruitless to try and anticipate every question that every oncall engineer might ask of their systems, but we can propose several which are common to all systems:

- What customers are impacted by the instability?

- Are we within our SLA for these customers?

- Are we meeting our SLO?

- Are they within their entitlement?

- How is the current state of the system typical?

- How is the current state of the system not typical?

- Has the function of our system changed in its larger system?

- Has this happened before?

- If this happened before, what did we do about it?

- If this hasn’t happened before, why not?

- What is our Recovery Time Objective for this instability?

- Will we meet our Recovery Time Objective?

- If not, why not?

- What else do we need to know?

A healthy system will be generating telemetry sufficient to answer all of these questions when asked. A robust system will include non-human controllers which codify at least some of these questions and automatically issue corrections based on the answers.

It is inevitable that we will ask new questions that cannot be answered by existing telemetry; this is precisely what occurs when automated corrections fail to stabilize a system: we ask why weren’t the automated corrections sufficient? But if we reach that point and lack the observability to answer these most common questions, we will not have the degree of control necessary to adapt to the new situation.

Observability for Steady-State Operations

It is difficult to improve observability into a system while it is unstable, as any engineer that has attempted to hotfix an unstable service to add additional metrics without causing additional instability can attest. Thus as operators it is our responsibility to regularly review our telemetry and improve it when the system is stable; this is one aspect of Hollnagel (2016)‘s view of a system adjusting its function to unexpected opportunities.

Recall that our goal is to maximize stability of our systems to the limits of our control. To do this we must increase our control, and to do that we must improve our observability into our systems. Here are some questions to ask of a stable system that can drive these iterative improvements:

- Is the system stable?

- Does the system implementation match its function in the external system?

- Does our predictive operations model describe the system as observed?

- What are the risks to stability?

- How do we preserve stability at lower operational expenditure?

- How do we shift corrections from human actors to software agents?

- What telemetry is missing (what questions can’t we answer)?

- How do we improve the signal:noise ratio of our telemetry?

- What controls are missing; that is, what telemetry are we not acting on?

- What controls should be removed?

- How can we make actors more predictable?

- How can we make nodal output more predictable?

As Allspaw (2019) notes, resilience engineering as it pertains to software engineering is in its infancy, and as such a practical model is well beyond the scope of our current inquiry. We intend these questions to be a place to begin working on observability through the lens of control theory, only. As we use them to investigate our systems, the value of changes made to the system can be judged by their effects on control whenever instability occurs. If our control is improving, our observability must be improving also; that is, we are extracting more meaning from our telemetry by asking, and answering, more and better questions that we could previously. For every proposed change therefore we must ask, does this change facilitate greater control of the system? If the answer is not in the affirmative, it may be the wrong change to make (or at least it is a change that does not improve observability).

The challenge is that this work — improving control by executing on observability — must be done in absentia of economic justification (Allspaw, 2019). Its only practical value is in its application in unpredictable scenarios, which by definition may never occur. Organizations that seek to exert greater control over their distributed systems must undertake this work knowing that it may never be used. Until it is.

Conclusion

To quote the statistician George Box, “All models are wrong, but some are useful;” this is certainly true of the model we have described. The application of control theory to the operations of distributed systems is a useful lens through which we can view the aims of resilience engineering in a structured manner, and provide a framework for discussing these concepts, taking goals on them and identifying real work that can be done to achieve them. We have shown how a complex distributed system with many individual components can be categorized and classified into discrete actors that follow their function, rather than form; and placed within the context of the environment in which they operate, how the establishment of a predictive operational model can help us manage these systems, and how the tension between real world observations and the model we use can provide insights into the structural weaknesses of our systems and identify opportunities to improve. However this represents the very smallest of beginnings; as (Bertalanffy, 1969) states, “Of course, the change in intellectual climate which allows one to see new problems which were overlooked previously, or see the problem in a new light, is in a way more important than any single application” (p. 99). Whether the current model has utility in real-world application remains to be seen, and a future body of case work will provide practical insights no doubt overlooked herein.

References:

Ackoff, R. (1993). From Mechanistic to Systemic Thinking [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yGN5DBpW93

Allspaw, J (2019). Resilience Engineering: The What and How [Video file]. Transcript retrieved from https://devopsdays.org/events/2019-washington-dc/transcripts/resilience-engineering.pdf

Bertalanffy, L. v. (1969). General systems theory: Foundations, development, applications ( Revised Edition ed.). New York: George Braziller Publishing.

Hollnagel, E. (2016). Resilience Engineering. Retrieved from http://erikhollnagel.com/ideas/resilience-engineering.html

Marsiglia, A. (2009). Synthesis of Classic Writings on Systems Theory: Bertalanffy’s General Systems Theory. Retrieved from http://www.lead-inspire.com/Papers-Articles/Leadership-Management/Synthesis of System Theory Writings.pdf

Mayr, O. (1969). The Origins of Feedback Control. Clinton, MA USA: The Colonial Press, Inc.

Vogels, W. (2016). 10 Lessons From 10 Years of AWS, Retrieved from https://www.allthingsdistributed.com/2016/03/10-lessons-from-10-years-of-aws.html

Zhong, Wan-Xie (2004). Duality System in Applied Mechanics and Optimal Control. Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers

Copyright (c) Greg Boyington, 2019. All Rights Reserved.